Here’s a nice little write up at Wonderful Machine’s blog. The original post can be found here.

A leap of faith that companies take from time to time involves marketing themselves to demographics outside their main consumer base. It’s a risk, to be sure, considering the number of resources these companies need to invest in this kind of advertising push. This is what fishing rod manufacturer Sage Fly Fish, with the help of photographer Cameron Karsten, is trying to do.

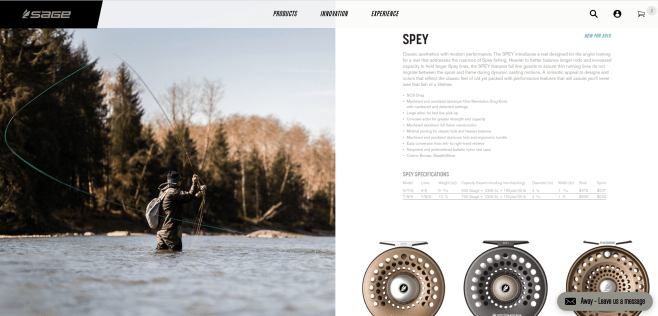

Fly fishing is mostly known as a retiree’s sport, so Sage wants to break the old model and show imagery of all persons young and old, as well as shots of both seasoned anglers and novices.

Sage is a leading brand in this market, and it sells products for a wide variety of fishing locations, from freshwater streams to saltwater oceans. As a result, Cameron has done a good bit of traveling in and out of the country.

Every season, Sage utilizes their imagery for the different seasonal fishing taking place around the globe. For example, there is a heavy winter steelhead run in the Pacific Northwest, so new products are unveiled for this technique during this season.

These images are shot months in advance and are rolled out within their appropriate season, used on everything from social media channels to print runs in select fly-fishing periodicals. Their also published on the web for online sales and made into big banners for trade-shows.

Of course, fishing takes a ton of patience, but that’s to Cameron’s benefit. The hours-long process allows him to think creatively and try new things, which helps both him and the client.

Fly fishing is a very slow methodical process, whether sighting fish, working a hole in the river, or spey casting a stretch of nice running water. As a photographer, I have a lot of time to work the angles, get the shot of the cast, and then try something unique, creative, out-of-the-box.

During these shoots I’m a fly-on-a-rock, following the angler as he fishes various holes and ripples, chasing tailing fish on the flats, or doing the basic mechanics of tying on a fly, changing line, or releasing a fish. The goal is to capture not only the cast, but the culture and story of a fly-fishing angler.

In getting the whole picture, Cameron sometimes has to create wide shots for specific uses. His arresting panoramas perfectly capture all there is to soak in while fishing in some gorgeous places, and they’re used quite nicely by Sage.

These wide shots are meant for large banner presentations at trade-shows or on the web. The goal is to show the beauty of the location with the subject within the setting. To set these up, I place the individual within the space and allow my eye to find the perfect positioning so I can capture the perfect cast that represents Sage and the sport. I then shoot plates surrounding the subject, which creates a large banner image once stitched together in PhotoShop. The images often render 4GB or more in size.

Another nice development within these shoots is the sense of camaraderie amongst the brands that market products aimed at the same people. Where Sage wants to sell equipment, Patagonia wants to sell merchandise, and YETI wants to sell gear. As the person who mixes everything together, Cameron can produce batches of imagery that tell a full story and help each organization.

The great thing about this culture of fly fishing is there are so many high-end companies who want to work together — brands that have similar stories in their own light but look to affiliate with one another due to their experience, quality, and value. On a lot of these fly fishing campaigns, I’ve been able to bring on different partners. Companies like Patagonia and YETI have fantastic gear for all of these environments. So, to bring on these brands is wonderful and makes the whole adventure complete with quality equipment.

Below is a link to a booklet we shot on-location in Idaho, and more work can be found at www.CameronKarsten.com.

It was dripping; the sun shrouded by cloud, the cloud returning to damp where dew ran with rain and rain soaked into thick rivulets of sand. All these paths led to a tempest of gray salt, growling together as an always-temperamental Northwest coastline. We shouldered our loads, pack mules down scree slopes, each step sinking into the shifting earth.

It was dripping; the sun shrouded by cloud, the cloud returning to damp where dew ran with rain and rain soaked into thick rivulets of sand. All these paths led to a tempest of gray salt, growling together as an always-temperamental Northwest coastline. We shouldered our loads, pack mules down scree slopes, each step sinking into the shifting earth. Walking off the beach, skin tensing from the drying salt water, we turned and marveled at the temptation we left, but the promise of additional companions and a new adventure forced us back through the thick fern fronds and salal fields that guarded those secrets. We pulled into a freshwater bay to meet our other companions: Sam from Ocean Beach and Kris from hometown.

Walking off the beach, skin tensing from the drying salt water, we turned and marveled at the temptation we left, but the promise of additional companions and a new adventure forced us back through the thick fern fronds and salal fields that guarded those secrets. We pulled into a freshwater bay to meet our other companions: Sam from Ocean Beach and Kris from hometown. Each canoe weighed heavy in the soft mud as the four of us laughed, organized and inspected everything. We had the gear and a malleable plan. Now we needed waves. Under a milky afternoon, still with high, wafting clouds, we embarked waters teaming with perch, pikeminnow, coastal cutthroats and kokanee to a point of cache and then further across deeper waters into the middle of nowhere.

Each canoe weighed heavy in the soft mud as the four of us laughed, organized and inspected everything. We had the gear and a malleable plan. Now we needed waves. Under a milky afternoon, still with high, wafting clouds, we embarked waters teaming with perch, pikeminnow, coastal cutthroats and kokanee to a point of cache and then further across deeper waters into the middle of nowhere. Camp One welcomed us with an evening storm that lulled us to sleep with the soft, synthetic patter of raindrops on nylon. As we emerged into the light of day two, all was sodden, the leaching wetness of winter – the rotting season. Nothing remained dry outside our expedition packs. And as we cooked packets of instant oatmeal, we scanned the angry horizon for signs of contour.

Camp One welcomed us with an evening storm that lulled us to sleep with the soft, synthetic patter of raindrops on nylon. As we emerged into the light of day two, all was sodden, the leaching wetness of winter – the rotting season. Nothing remained dry outside our expedition packs. And as we cooked packets of instant oatmeal, we scanned the angry horizon for signs of contour. Camp Two was a sand bank, a small cove of great fortune that was ours, alone, for four days. From this vantage point, we watched the sea. Corduroy lines of swell marched like infantry. That clean A-frame was gone, replaced by a meaty little slab.

Camp Two was a sand bank, a small cove of great fortune that was ours, alone, for four days. From this vantage point, we watched the sea. Corduroy lines of swell marched like infantry. That clean A-frame was gone, replaced by a meaty little slab. These instances were often the most memorable, the time away from time where scrutiny of an industrial civilization weighed weight upon a ticking time bomb. Omniscient and harmonious was the mind, free to soar in solitude like the eagles above, and glide like a Pelican upon the updraft of rolling sea. We found more scat; bear, raccoon, coyote. We stepped over the skins of dogfish and collected Japanese plastics from disasters far away and seemingly long ago. Then we ended.

These instances were often the most memorable, the time away from time where scrutiny of an industrial civilization weighed weight upon a ticking time bomb. Omniscient and harmonious was the mind, free to soar in solitude like the eagles above, and glide like a Pelican upon the updraft of rolling sea. We found more scat; bear, raccoon, coyote. We stepped over the skins of dogfish and collected Japanese plastics from disasters far away and seemingly long ago. Then we ended. The morning of our departure, the sun broke and alighted our long playful shadows across the sand as we slipped northward towards Camp One, back through the fern forest and salal fields to a freshwater point. We had work to do.

The morning of our departure, the sun broke and alighted our long playful shadows across the sand as we slipped northward towards Camp One, back through the fern forest and salal fields to a freshwater point. We had work to do. We slid onto the sandy beach, found our stores of wood and hardware, beer and fire, and set to work. Skyler repaired the lean-to with his fashioned door. Sam built a hot fire of cedar wood and lava rock, while Kris fashioned a shovel to carry the stones from heat to shelter. Over the course of three hours we took turns bathing in the sweet sweat of a traditional sauna, removing all traces of bitter cold from our bones. And then just before dusk we set off for home, just as we had done days prior when we entered the shadows of fern and salal that guarded the undiscovered surf in the wilds of our backyard.

We slid onto the sandy beach, found our stores of wood and hardware, beer and fire, and set to work. Skyler repaired the lean-to with his fashioned door. Sam built a hot fire of cedar wood and lava rock, while Kris fashioned a shovel to carry the stones from heat to shelter. Over the course of three hours we took turns bathing in the sweet sweat of a traditional sauna, removing all traces of bitter cold from our bones. And then just before dusk we set off for home, just as we had done days prior when we entered the shadows of fern and salal that guarded the undiscovered surf in the wilds of our backyard.