It rained and then it poured. With STORMR gear, the woodsmen were kept warm as a low ceiling of clouds passed, and dry as the hiking became arduous with sweat and fatigued. Heavy ferns draped in our path while carpets of green moss stretched before us. Animal trails were easy to find, their beaten paths the only thing breaking the wildness of the Hoh Rainforest. These led us to the wide open swaths of America’s logging industry.

STORMR Deer Camp: Into the Hoh Rainforest (Pt. I)

Recently, I ventured into the Hoh Rainforest with STORMR foul-weather gear for a 4-day 3-night adventure. With four woodsmen we explored a sodden mossy wilderness furthest from humanity. These are the western edges of the Olympic Peninsula; a place so remote and ecologically diverse that it could be considered its own evolutionary island.

What we were in search of was the elusive black-tail buck. What we discovered were torrential downpours, rivers full of returning steelhead and King salmon, as well as pockets of clear-cut forests amidst pristine woodlands of idyllic nature where migratory elk bugled near the trails of deer, bear, and cougar scat.

For more visit www.STORMRrusa.com and www.CameronKarsten.com

Puget Sound Restoration Fund: The Oyster Harvest

Oysters are delicious, but they’re also highly important to our marine ecosystem. They’re natural filtration systems, removing toxins and cycling nutrients back into the water that help combat pollution. Oysters within the Puget Sound are also some of the first species to feel the effects of a new threat called Ocean Acidification (OA). As the ocean becomes more acidic due to decreasing pH levels from human industrialization, oyster seed shells begin to dissolve causing holes, disease and early death.

Puget Sound Restoration Fund (PSRF) is helping restore these mollusks by planting native oyster beds throughout Puget Sound. They’re creating a community of oyster harvesters through their CSA program, as well as partnering with research institutes to further study and treat the effects of OA. On an early morning on Bainbridge Island, Washington local volunteers gather to take advantage of the low tide and collect the native oysters.

For more visit the Ocean Acidification Project

Pastorals Gone East

“Simplicity is the glory of expression.” -Walt Whitman

A road trip last summer into the high plains off the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains.

For more work please visit http://www.CameronKarsten.com

All Across Africa – Designs by Nightingale Handmade

Earlier this year I spent two weeks with All Across Africa helping them rebrand their work throughout Rwanda, Uganda and Burundi. With their new website up and running, I’ve fallen in love with Margaret’s (Nightingale Handmade) designs on a few of the images created for AAA. Enjoy these beautiful postcards and go visit www.AllAcrossAfrica.org to make a purchase for the women of East Africa.

STORMR Campaign: Olympic Wildness Pt. III

After a night’s rest, the men returned to the waters, this day wading into the flowing waters of the Olympic tributaries. Their STORMR foul-weather gear proved protective and durable as fishermen Simon Pollack and Skyler Vella threw flies before returning steelhead and salmon.

After a night’s rest, the men returned to the waters, this day wading into the flowing waters of the Olympic tributaries. Their STORMR foul-weather gear proved protective and durable as fishermen Simon Pollack and Skyler Vella threw flies before returning steelhead and salmon.

For a complete portfolio, please visit www.CameronKarsten.com

Africa Transporting

While on assignment in Africa for the first two months of 2014, I was captivated by the way humanity transports itself and its’ cargo. This new project highlights the unique and massive modes of transportation the African continent moves about. From West African countries Benin and Togo to East Africa’s Rwanda, Uganda and Burundi, all modes are the same: extreme, beautiful and oddly delicate.

The paddle boat is an easy means of transportation for fisherman and the obvious choice for floating villages – Lake Tanganyika, Bujumbura, Burundi.

The paddle boat is an easy means of transportation for fisherman and the obvious choice for floating villages – Lake Tanganyika, Bujumbura, Burundi.

A woman paddles with her child in the early morning to the floating market of Ganvie – Lake Nakoue, Ganvie, Benin.

A woman paddles with her child in the early morning to the floating market of Ganvie – Lake Nakoue, Ganvie, Benin.

Bikes are cheap and easy to fix, but the roadway and traffic can be horrendous – Bujumbura, Burundi.

Bikes are cheap and easy to fix, but the roadway and traffic can be horrendous – Bujumbura, Burundi.

Oil drums being transported through downtown Bujumbura, Burundi.

Oil drums being transported through downtown Bujumbura, Burundi.

Bicycles are ubiquitous, and so are mountainous hills, in northern Burundi. Men hitch rides by grabbing onto the sides and rear of large lorry trucks heading up and heading down – Northern Burundi.

Bicycles are ubiquitous, and so are mountainous hills, in northern Burundi. Men hitch rides by grabbing onto the sides and rear of large lorry trucks heading up and heading down – Northern Burundi.

Many young men hop lorry trucks when traveling up and down the northern hills of Burundi – Northern Burundi.

Many young men hop lorry trucks when traveling up and down the northern hills of Burundi – Northern Burundi.

A long walk to the border from Bujumbura, Burundi to The Democratic Republic of Congo. Burundi is ripe with agriculture, so many travel to the border to sell their harvests to Congolese – Bujumbura, Burundi.

A long walk to the border from Bujumbura, Burundi to The Democratic Republic of Congo. Burundi is ripe with agriculture, so many travel to the border to sell their harvests to Congolese – Bujumbura, Burundi.

In the countryside, the movement of people on foot often looks like a mass exodus. People walk miles to crop land, distant markets, and back home within a day – Virunga Mountains, Rwanda.

In the countryside, the movement of people on foot often looks like a mass exodus. People walk miles to crop land, distant markets, and back home within a day – Virunga Mountains, Rwanda.

Slopes are carved out with foot paths that lead to neighboring villages and fields – Virunga Mountains, Rwanda.

Slopes are carved out with foot paths that lead to neighboring villages and fields – Virunga Mountains, Rwanda.

Dotting Africa are a host of infrastructure projects, most sponsored by Chinese firms. Here a Djagli, a mythical bird in Vodou culture, rests between performances – Allada, Benin.

Dotting Africa are a host of infrastructure projects, most sponsored by Chinese firms. Here a Djagli, a mythical bird in Vodou culture, rests between performances – Allada, Benin.

An infrastructure project in Northern Burundi, which was washed out by the previous season’s flash floods – Northern Burundi.

An infrastructure project in Northern Burundi, which was washed out by the previous season’s flash floods – Northern Burundi.

A tea picker near Ngozi, Burundi walks home after a day’s work – Burundi.

A tea picker near Ngozi, Burundi walks home after a day’s work – Burundi.

An empty wheel barrel on the tea plantation – Ngozi, Burundi.

An empty wheel barrel on the tea plantation – Ngozi, Burundi.

A young boy fishing on Lake Nakoue – Ganvie, Benin.

A young boy fishing on Lake Nakoue – Ganvie, Benin.

Along a construction road, young boys and men haul bananas to roadside stands offering produce, charcoal grilled corn, meats, and assorted snacks – Northern Burundi.

Along a construction road, young boys and men haul bananas to roadside stands offering produce, charcoal grilled corn, meats, and assorted snacks – Northern Burundi.

Traffic careens and passes the two-lane highways, passing villages, bustling markets and school courtyards. Traffic hazards are many for motors, cyclists and children heading to and from school – Northern Burundi.

Traffic careens and passes the two-lane highways, passing villages, bustling markets and school courtyards. Traffic hazards are many for motors, cyclists and children heading to and from school – Northern Burundi.

For more visit http://www.CameronKarsten.com

Vodou Footprints: A Faraway Land in Benin’s Cradle of Vodou

Geography, for many Americans, is that daunting and embarrassing mystery—a dim knowledge largely confined to wartime allies, historical enemies, and the occasional topical hotspot. Beyond this so-called important handful—Western Europe, the Middle East, possibly China or Japan—everything else is clumped together into a world of unknowns.

When I told acquaintances of my impending trip, the average response was somewhere between hesitance and puzzlement. Like a jargoning doctor to the common patient, my words didn’t ring many bells.

Well, perhaps Benin is a faraway land.

Admittedly, I too couldn’t place Benin in its exact location prior. West Africa, I’d say evasively, somehow hopeful that several nations would willingly surrender their unique identities to their greater region. Technically, I wasn’t wrong. But not surprisingly, I soon discovered that Benin deserved far more respect and scrutiny than I had originally expected. Take a closer look and you’ll begin to unravel a majestic tangle of complexity and misconception.

Benin borders Nigeria’s western edge, touches Togo’s eastern boundary, and supports Niger and Burkina Faso above. It is one of those tiny West African countries that stretch north to south. Sneeze and you’ll miss it. In fact, picture Africa’s western shoreline as a nose. Benin sits just beyond where the mouth and the nose would meet—at the nostrils, if you will—a sliver of land anchored by the fabled Bight of Benin.

And then there’s magic. In the West, the word conjures up David Blaine, television’s greatest living magician. A levitating, fire-breathing, death-defying illusionist. A beloved celebrity of record-setting endurance. A talent, no doubt. From the Beninese perspective, however, he is not a man of magic. Call him master of deception. Magic in Benin is a way of life.

Everywhere there is magic. It’s in the red earth of the landscape, the throbbing fury of the sun, and the relentless currents of the great flowing rivers. It’s their religion—a religion in which the interactions between nature and humanity are cherished and respected every day. Magic is Vodou. And with 4,000 years of magic backing it up, Benin is the undisputed cradle of Vodou.

Personally, I believe in magic, both as a form of deception as well as a supernatural expression of the energies beyond ordinary comprehension. For millennia, Homo sapiens—the self-proclaimed wise man—has existed, evolved, and generally erred, all the while attempting to explain: What lies beneath? What forces create the churning seas of the ocean and the gyrating clouds of the sky? What energies course through veins and roots alike? Indeed, what does our cunning and craft amount to aside vast incomprehensibilities? Our attempts to solve breed yet further questions. No matter our advancements or industry, the sun still rises and the moon ever orbits to a language seemingly all their own.

Countless cultures have contrived to explain these fundamental phenomena. Some grow. Most fade beneath the all-consuming flames of war and oppression. And yet, incredibly, amidst the largest powerhouses of the world, there exists a small country—undeterred by the folly of others and sorely ravaged by the horrible histories of slavery—where the primeval practices still prevail and the honor of the mysteries of the world take precedence.

Cast aside the linear mindset and the textual teachings of the West. Simply observe what is before you and what has come to pass. Only then will you understand Benin. Here the supernatural and natural worlds converge; everyday occurrences take on special meanings; and the privileged traveler may join the setting sun into the obscurity of a secret and sacred society to appreciate the mysteries of what Benin declares its official religion: the worship of the Vodou.

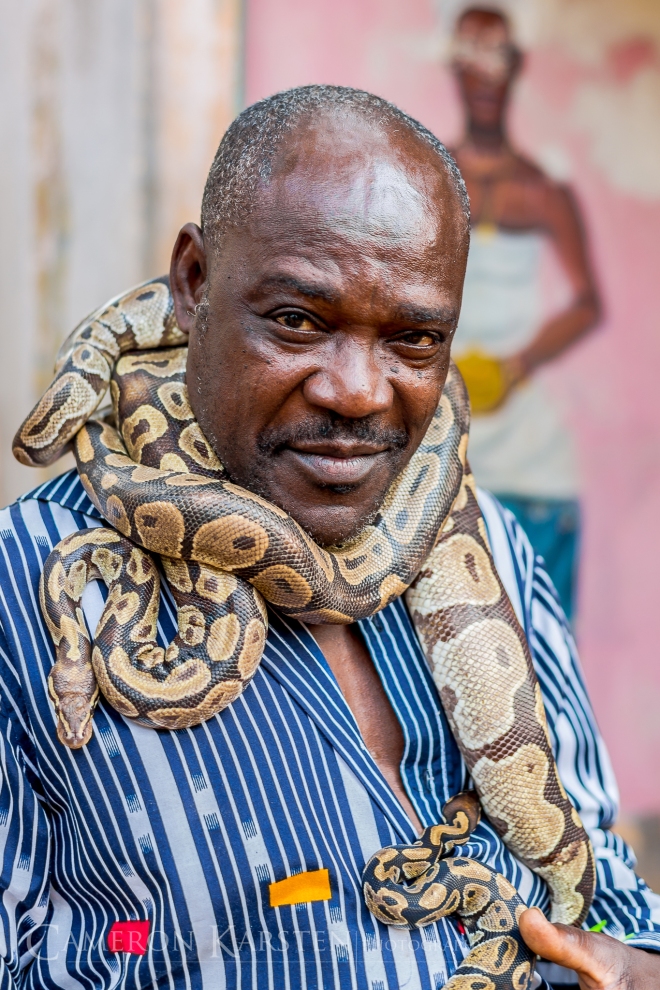

It is a world of shadow and dance. Of masks, scars, and tattoos. A country where Kings remain the Kings of Kings, and the leopard and snake reign in the household tale. Feel the pulsing rhythm of Vodou, transcend the merely tangible, and let the beat of the drum lift your mind into the realm of the metaphysical. Once you have crossed this threshold, once you have heeded this singular call, the world around can never be the same.

For us, there is no retreat. There is only the universal language of Vodou, and together we will drink from this bottomless cup.

Together we’ll reach a faraway land.

The Countdown Begins: The Origins of Vodun

I’m stoked that the countdown has begun! On December 31st, I’ll be heading to Benin, Togo and Ghana for roughly four weeks to begin a project about the origins and evolution of Voodoo. As a practice of animistic worship of spirits, Vodun is the official religion of Benin and considered one of its birthplaces. I’ll be traveling with friend and fellow photographer Constantine Savvides to create a multi-continent multimedia series including still, motion, audio and text. West Africa will be the first of several locations, retracing the spread of Voodoo via the slave trade to the West Indies and Americas, to its survival in today’s organized societies. These guys, chiefs of the old slave port in Badagry, Nigeria, know what I’m talkin’ about.

I’m stoked that the countdown has begun! On December 31st, I’ll be heading to Benin, Togo and Ghana for roughly four weeks to begin a project about the origins and evolution of Voodoo. As a practice of animistic worship of spirits, Vodun is the official religion of Benin and considered one of its birthplaces. I’ll be traveling with friend and fellow photographer Constantine Savvides to create a multi-continent multimedia series including still, motion, audio and text. West Africa will be the first of several locations, retracing the spread of Voodoo via the slave trade to the West Indies and Americas, to its survival in today’s organized societies. These guys, chiefs of the old slave port in Badagry, Nigeria, know what I’m talkin’ about.