After a night’s rest, the men returned to the waters, this day wading into the flowing waters of the Olympic tributaries. Their STORMR foul-weather gear proved protective and durable as fishermen Simon Pollack and Skyler Vella threw flies before returning steelhead and salmon.

After a night’s rest, the men returned to the waters, this day wading into the flowing waters of the Olympic tributaries. Their STORMR foul-weather gear proved protective and durable as fishermen Simon Pollack and Skyler Vella threw flies before returning steelhead and salmon.

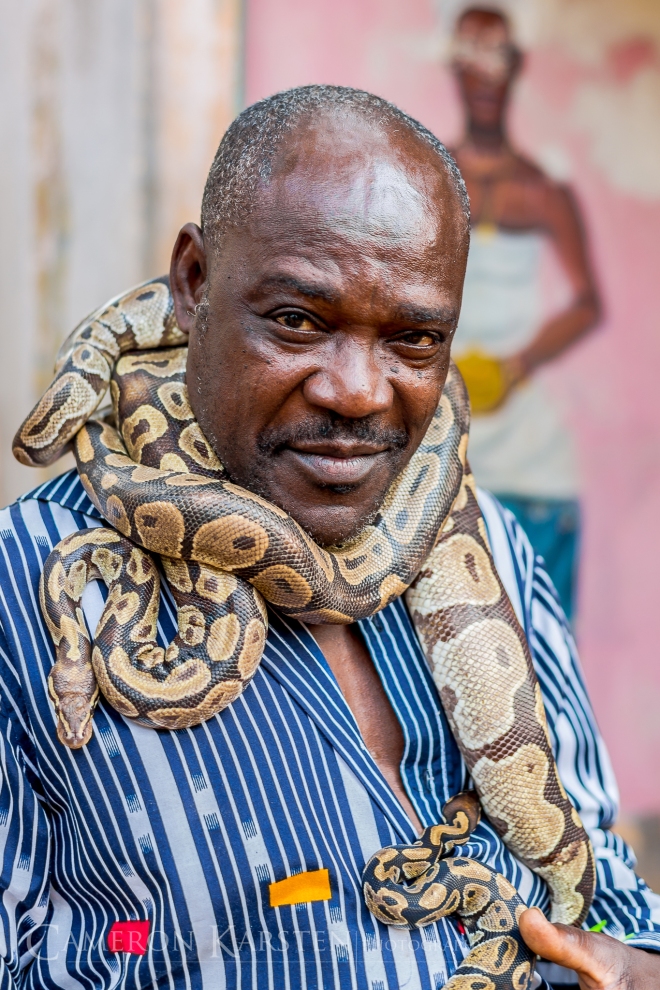

For a complete portfolio, please visit www.CameronKarsten.com