We speed north on a stretch of highway made just for the zemidjan, the motorbike of Benin that far outnumbers any other form of transportation in Cotonou. (For comparison, I’ve yet to see a single bicyclist.) In the local Fon language, the word means “take me quickly,” and they are not exaggerating. My driver weaves past other zems with mere inches to spare—honking, leaning, and accelerating in a mad death-defying ballet. It’s a test of stomach and sanity that I’ve never experienced. Plus, it’s early. We’re on our way to Ganvie, twenty minutes out of Cotonou. We leave the choked city with all its grinding muscle and hopeless might to enter a land of lizards, chickens, and goats—where you’re just as likely to see a Chinese migrant worker as a magical animal. And yes, there are plenty of both.

Ganvie is special, or so they like to recount. It’s a stilt village, built on things of legend. Known as the Venice of Africa, it is everything but. With wooden poles in place of granite columns, thatched walls instead of marbled halls, and corrugated steel roofs in lieu of frescoed cupolas, the village looks much like the rest of the African countryside—except that every structure floats above water. Fortunately, while the city’s foundation is only mildly intriguing, the history behind it is truly fascinating.

Benin, as both the willful cradle of the world’s most magical religion and the bound epicenter of one of mankind’s darkest hours, is a land like no other. Its past overruns with incredible lore, otherworldly powers, and inexplicable possibility. And Ganvie, that fabled stilt village, is a microcosm of this concentrated complexity.

At the height of the slave trade, the Kingdom of Dahomey reigned over present-day Benin with fearless authority. Opposition was swiftly dispatched, often through shackles and a sentence south into slavery. The Kingdom walls in Abomey are purportedly constructed of human blood, and the King’s throne built on the skulls of his Yoruba enemies. Of course, this ruthlessness was not without reward. In exchange for the capture and sale of slaves, Dahomey received weapons of warfare. To the Portuguese, a healthy grown man was worth twenty-one cannon balls; a woman or child, fifteen. Various rifles, jewels, and other luxuries were similarly bartered for the slaves that passed through the port village of Ouidah—more than 20,000 per year during its height in the 19th century. But for every ironfisted oppressor, there is a legendary resistor.

In 1717, the King of the Tofinu, a magical gent by the name of Abodohoue, felt the Amazonian warriors of Dahomey breathing hotly down his neck. Sensing imminent danger, he transformed himself into an egret and flew south from modern-day Allada over Lac Nakoue in search of a new homestead. What he knew was vital: the people of Dahomey had taken a religious oath promising that all humanly capture was acceptable unless it required passing over water. King Abodohoue kept this in his little egret brain and soon discovered an atoll of mud islands in the middle of Lac Nakoue.

Next, the question of transport crossed the bird-king’s mind: How would he safely ferry his people to the islands? Well, like any capable land-of-Vodou king, he simply morphed from egret to crocodile, swam over to the local bask of reptilians, and requested their assistance. The crocs heartily agreed, and King Abodohoue’s plan was set into motion. With local lumber and the backs of numerous newfound friends, the Tofinu people transformed the center of Lac Nakoue into the Venice of Africa, a suspended village that today boasts of nearly 30,000 residents (and is Benin’s number one tourist attraction).

We’re here to see it firsthand. Joined by Stephano, our guide, we jump aboard a hefty, water-soaked outboard canoe to the marooned village. Despite our eagerness, we don’t spot any descendants of the loyal crocodiles. (Later, we learn that their population has dwindled to a paltry few—a case of the tale outlasting the tail.) Passageways are filled with pirogues and paddlers, reeds and water lilies. Life is simple. Sustained by fish farming, traded goods, and the slowly rising costs of tourism, the people manage a relatively normal lifestyle, in contrast to the environs. We come. We go. In truth, the town doesn’t live up to its past.

Along the nearby shores of Lac Nakoue, however, sits a much more intriguing town. Rich with Vodou and layered with countless stories (many of which we’re hoping aren’t true), Abomey-Calavi has long been a must-visit stop following Vodou Footprints.

Except for a handful of curious anthropologists and open-minded theologians, the Western world places Vodou somewhere between pseudo-religion and marketable nightmare. It’s a doll probed with pins and needles. The musty pages of a leather-bound spell book. A dark evil force. Something to openly scoff at, but secretly question. More importantly, it’s equated with fear.

For this (as with copious other misconceptions), we can thank the silver screen. Beginning in the 1930’s, Hollywood started crafting a crude and compelling mixture of back-alley-New-Orleans Hoodoo with plantation-Haitian Voodoo. Replete with unlikely plots and zombie-inducing potions, these films convinced the terrified, uninitiated masses (outside of Vodou itself) that this was the actual religion—emphasis on the fear.

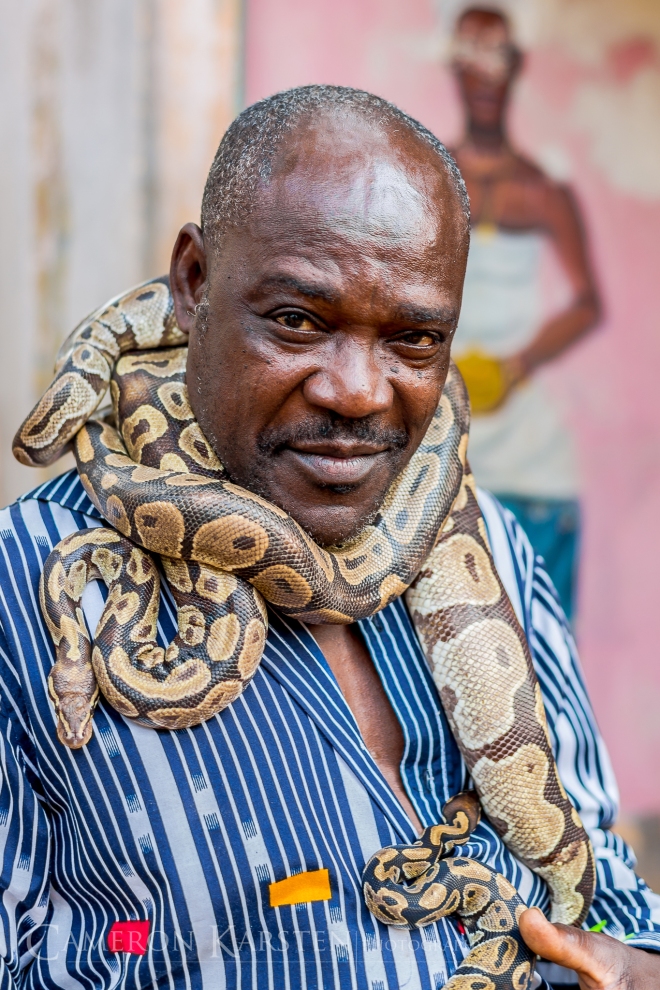

Vodou is, of course, less than these depictions would suggest, but in many ways more enriching and exciting. And crucially, Vodou is not to be feared—just as the police are not to be dreaded unless committing a crime. Some call it justice, others karma. In its stead, respect and prudence are superior traits. For the long-deceived Westerner, however, leaving the fear out of Vodou is easier said than done—especially in Abomey-Calavi, a town known for the unknown. After arriving on the shores of Lac Nakoue, we quickly disappear into its narrow passages. We’ve arranged a meeting with the king.

We aren’t quite trembling, but conversation has crawled to a tense halt. We enter a doorway, where we’re instructed to remove our shoes, socks, and shirt. Silently, we do as we’re told. Already, I feel like a child awaiting sentence outside the principal’s office. With our heads slightly bowed, we step inside the dark room.

We’ve heard stories of contamination; read about incurable and miserable plagues. I remember one tale and instinctively I scratch my forearm. Fleas. Everything we’ve read refers to fleas. The King of Abomey-Calavi is apparently infested with them. Carpets in the royal chamber are reportedly saturated with the miniature black parasites—a blood-sucking legion stealthily waiting beneath the shag for the white flesh of a foreigner. As I begin imagining my skin as the feast’s main course, I notice my partner with preparatory scratching of his own. I can’t help but picture our future together—collars tight around our necks, huddled on the floor of some quarantined windowless research lab.

We take a few more cautious steps.

Any one of those rumored tragedies would put an instant end to our journey, if not more. We’ve neither time nor funds for borax soaks or chemical treatments. But we’re here, and we’re ready to accept the risks. If you want access beyond the books and into the unknown, you don’t have a choice.

As my eyes adjust to the dimly-lit room, I see no carpet. No fabrics of any kind—only woven mats and further, a gently waving waxy palm. Slowly, I begin to make out a large seated form. I take a final deep breath, and the fleas fly from my mind. We are face-to-face with our first Vodou king.